The

Exhibition for this Artefact was Thursday 1st to Friday 2nd

June 2006,

Reading Campus, TVU

Introduction

This

module was split into two sections: Proposal Presentation (completed)

and Development of an Artefact. This essay seeks to explain

the development of concept and give a post-analytical summary

of the exhibition for the artefact ‘Miniature Index’.

Most of this will be done within this essay but an accompanying

short film on DVD will support this work and can be found inside

the submission pack. If you are reading this without the pack

email: paul.glennon@tvu.ac.uk

The

logic behind splitting this module into a project proposal and

final artefact is simple and effective – present an emerging

idea halfway through the module, then develop that idea into

an actual working artefact. As the artefact for this work culminated

in an exhibition, it is recommended that the DVD is watched

either before or after reading this essay.

Beginnings

The

initial proposal started as a film in a box. The film explained

intentions through the use of a small screen implanted inside

a hand-made box isolating the screen. A documentary-style short,

filmed on a mobile, entitled ‘Paul’s Wee World in

a Box’ was the actual mobile phone screen itself, embedded

inside the structure. View this link.

The point of the box was to give people an insight into the

mind of Paul Glennon.

The box was influenced by Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Valise’

(Suitcase) series that house miniature re-creations of his artworks.

In ‘Paul’s Wee World in a Box’, the structure

became a miniature ‘one person film theatre’. (The

word ‘Miniature’ came from feedback from Mike Barker,

the tutor for this module, in reference to the small screen

world we are living in.)

The

proposal went well, but further development of the box was too

difficult. The box seemed to have served its purpose and the

concept needed to be pushed. The best option was to move the

contents, keeping the general idea but exploring greater possibilities.

Literary devices were used for inspiration especially the complex

thought processes in James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’.

Jeri

Johnson, a Fellow in English at Exeter College, Oxford, wrote

in her introduction to James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’

about the use of ‘interior monologue’:

‘a

literary technique capable of presenting directly without aid

of an intrusive omniscient narrator the most intimate, often

half-formed, only half-verbalized, thoughts of a character…’

(Johnson, 1998, p. 20)

Johnson

warns the reader not to confuse this with a ‘stream of

consciousness’ (a term first coined by the American philosopher,

William James) which describes the mechanistic workings of consciousness

in an individual as opposed to thoughts spilling onto a page.

For the development of the ‘Miniature Index’ a decision

was made to work somewhere in between the two, jotting down

random thought process when working on a creative problem, then

bringing order to the thoughts by indexing them into alphabetical

order.

Extending

and Exploring the Concept

To help with this it was deemed relevant to follow the ‘art

history trail’, after studying Duchamp’s ‘Valise’

artworks (see Project Proposal) – this led to one artist

in particular. Joseph Kosuth (b. 1945) was part of the ‘Siegelaub’

Conceptual Art movement in the 60’s. He was concerned

with Linguistic Philosophy, in particular dictionary definitions

and the basic use and understanding of ‘words’.

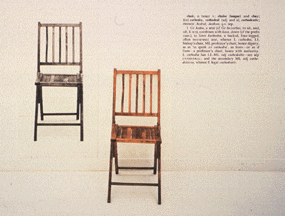

‘One and Three Chairs’ (1965/6 – below) is

an excellent example – in this work we find an actual

chair, a picture of a chair and a dictionary definition printed

on the gallery wall.

Kosuth

seems to question art in a basic way but at the same time seeks

to bring clarity to meaning.

‘The

task of art consists in constantly questioning its own essence

and, in extended analysis, to contribute to the clarification

of the question of what art is.’

(Marzona, 2005, p. 72)

As the end of this module began to loom

the non-movement of ‘Paul’s Wee World in a Box’

became a greater problem – the exact question of ‘What

is Art’ became problematic. However, in observing the

above comment about Kosuth it was noted that instead of a question

being asked, a statement might well be being made: not ‘What

is Art?’ but a suggestion of ‘What Art is’.

This

led the study into the difficult and confusing world of ‘Tautology’

(a statement that is necessarily true, The Concise Oxford Dictionary).

Kosuth explains this with the following: ‘art idea (or

work) and art are the same and can be appreciated as art without

going outside the context of art for verification.’ (Marzona,

2005, p. 72). There are many ways in which one can interpret

this statement, one perhaps being the seeking of clarification

from a given reference point when creating something (such as

art).

So,

in ordering ‘thought processes’ to be turned into

an art piece, it seemed advantageous to find a reference point

related to the basic principles of ‘the creative process’.

In the sketchbook for this module, words were jotted down describing

Paul Glennon’s creative process. The following words emerged:

Words,

Drawing, Sketchbook, Film, Exhibition, Discussion, etc.

These

words came quite easily and immediately the recollection of

Bruce Nauman’s work came into mind:

‘Work,

Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work,

Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work, Work,

Work,…’

(Nauman, 2004, p. 31)

Last

year Bruce Nauman filled the Turbine Hall in the Tate Modern

with his sounds in an exhibition called ‘Raw Materials’.

The hall was simply filled with large speakers playing sounds

from his collected artworks. An excellent Web site accompanied

this exhibition which allowed you to hear the sounds and see

the artworks in their original state: click

here. One piece in particular comes to mind. From the Clown

Torture Series:

‘Double No’, 1998

‘Double No’, 1998

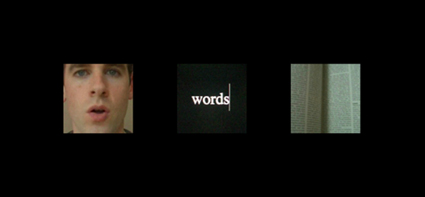

The use of actual people in ‘Double

No’ makes the piece real. What better way to witness the

creative process of Paul Glennon than by direct observation

of his face speaking the words into a video camera? This made

up the first frame in the final artefact film.

By

now a clear interest in words had emerged and as this MA is

one of Computer Arts, what better way to create the words, while

they are being said, than by typing them? Not just typing them,

but recording the very keyboard being tapped and a video of

the letters appearing on a monitor. The third picture was simply

a physical representation of ‘words’ videoed from

a book. Thus a triptych film with movement and sound was born.

From

the observed creative process of Paul Glennon eleven key words

emerged in the sketchbook, and from the template of the first

triptych the entire piece was completed quickly. (See attached

CD with FLASH file. Note, this is only a part of the overall

artwork and should be viewed in the installation piece ‘Miniature

Index’.)

The

Actual Artefact

The

final decision to be made was how to display this video loop.

The original box had served its purpose so a new device had

to be constructed. Or did it? Within the sketchbook for this

module, many token ideas are drawn with the intention of solving

this issue, most of them unsuccessful. They generally tended

to look like ‘Punch and Judy’ stages that were designed

for the viewer to stick their head into – too elaborate!

It was not until the original starting point was reinvestigated

again that the idea took hold.

Within

the Project Proposal the hiding or isolating of the screen came

from a childhood obsession with a 3-D View Master. Children

could peer into the binocular-style headset whilst flicking

the disks to see the various images, giving them the opportunity

to shut themselves off from the surrounding world (for me West

Belfast, in the 70s and 80s). When you look inside the View

Master, peripheral vision is blocked due to the design of the

head set, thus making you look harder at the image. The idea

of making people look hard at moving image seemed important

– we see so much television and film but are we really

looking any more? It seemed important to make the observers

of this piece of work look harder and in turn reveal the working

processes in a more focused way.

The 3-D View Master was not an option as an

actual thing to look through, so, personal objects from the

past were hauled out of storage. An old filing cabinet that

had been lying around with no handle (it had been ripped off

by me in a fit of rage over three years ago) offered obvious

connotations but also harked back to the classic ‘ready-made’

artwork. With a laptop fitting neatly into the top drawer, ‘Miniature

Index’ was born. (The title of the piece had to be bashed

out in a tutorial with Mike Barker!) The best thing about the

filing cabinet was the height – it was a half size office

piece, and even on a plinth it required the viewer to bend down

to look in.

Exhibition

& Evaluation

The

exhibition of this work offered an opportunity to see the work

in situ. Colleagues and students entered the room; some were

puzzled at first, and then, hearing the sound were drawn to

peek inside. Most people bent down but some knelt in front of

it.

A

comment box on the side proved beneficial in collecting written

feedback (see DVD) and the actual sketchbook was popular with

visitors (pages can be seen on the Module 3 section at this

link.)

As

part of the Private View a Performance piece was worked into

the evening. The work was projected onto the wall and people

were videoed with Paul Glennon’s face on theirs (see DVD).

This was good interaction and encouraged more debate during

the evening.

The

most memorable thing about the evening was the fact that people

had to work hard to see the film, thus were more focused.

Final Note

This is the beginning not the end of this work. Recently the

filmmaker Peter Greenaway was quoted as saying that the potential

of film has not yet been explored to its maximum. The ways in

which we actually view moving image must be explored more if

we are to break free from what Greenaway calls a ‘steam-driven

19th century template of theatre and literary adaptation’.

Only then might we be able to engage with ‘the great art

of painting in motion’ (quoting Rudolf Arnheim in his

1957 book ‘Film as Art’).

References

Arnheim,

R, (1957) Film as Art

University of California Press

Bradshaw,

P (2006) Call that a Movie?

The Guardian / G2 / 16th May 2006 / p. 22 - 23

Joyce,

J (1998) Ulysses

Oxford World’s Classics / Edited with an Introduction

and Notes by Jeri

Johnson

Morzona,

D (2005) Conceptual Art

Taschen

Nauman,

B (2004) Bruce Nauman – Raw Materials

Tate

SLIDES

FROM THE EXHIBITION

Thank

you to all who helped and came to the Exhibition!